Resources

Patients and Families

Information for Clinicians

Selected References

- Grant D, Abu-Elmagd K, Reyes J, et al. 2003 report of the intestine transplant registry: a new era has dawned. Ann Surg 2005;241:607-13.

- Grant D. Current results of intestinal transplantation. The International Intestinal Transplant Registry. Lancet 1996;347:1801-3.

- Abu-Elmagd KM, Costa G, Bond GJ, et al. Five hundred intestinal and multivisceral transplantations at a single center: major advances with new challenges. Annals of surgery 2009;250:567-81.

- Abu-Elmagd KM, Kosmach-Park B, Costa G, et al. Long-term survival, nutritional autonomy, and quality of life after intestinal and multivisceral transplantation. Ann Surg 2012;256:494-508.

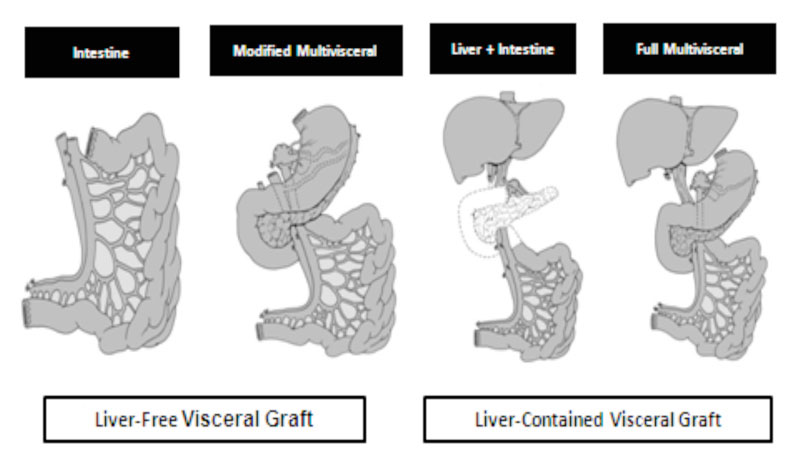

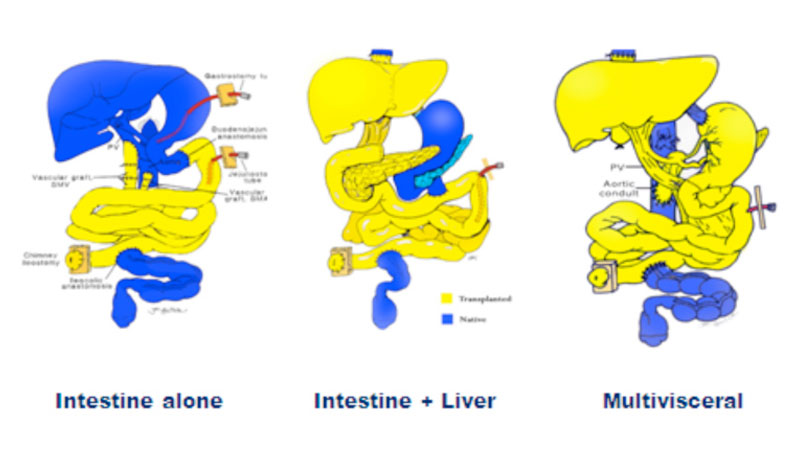

- Abu-Elmagd KM. The small bowel contained allografts: existing and proposed nomenclature. Am J Transplant 2011;11:184-5.

- Oliveira C, de Silva N, Wales PW. Five-year outcomes after serial transverse enteroplasty in children with short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Surg 2012;47:931-7.

- Ngo KD, Farmer DG, McDiarmid SV, et al. Pediatric health-related quality of life after intestinal transplantation. Pediatr Transplant 2011;15:849-54.

- Dar W, Agarwal A, Watkins C, et al. Donor-directed MHC class I antibody is preferentially cleared from sensitized recipients of combined liver/kidney transplants. American Journal of Transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons 2011;11:841-7.

- Abu-Elmagd KM, Wu G, Costa G, et al. Preformed and de novo donor specific antibodies in visceral transplantation: long-term outcome with special reference to the liver. Am J Transplant 2012;12:3047-60.

- Fishbein TM. Intestinal transplantation. The New England Journal of Medicine 2009;361:998-1008.

- Pironi L, Staun M, Van Gossum A. Intestinal transplantation. The New England Journal of Medicine 2009;361:2388-9; author reply

- Sudan D. Long-term outcomes and quality of life after intestine transplantation. Current Opinion in Organ Transplantation 2010;15:357-60.

- Farmer DG, Venick RS, Busuttil RW. Improving outcomes after intestinal transplantation at the University of California, Los Angeles. Clin Transpl 2010:245-52.

- Mazariegos GV, Steffick DE, Horslen S, et al. Intestine transplantation in the United States, 1999-2008. Am J Transplant 2010;10:1020-34.

Social

Contact

Address

International Intestinal Rehabilitation & Transplant Association

c/o The Transplantation Society

740 Notre-Dame Ouest

Suite 1245

Montréal, QC, H3C 3X6

Canada